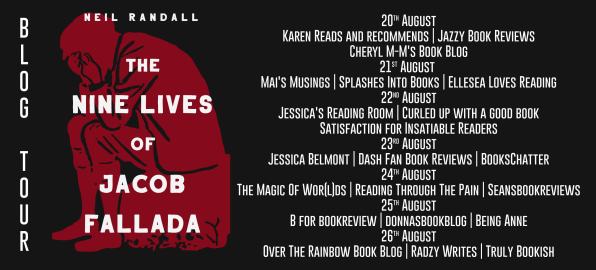

When Rachel at Rachel’s Random Resources invited me to join the blog tour for The Nine Lives of Jacob Fallada by Neil Randall, I rather wished I’d been able to find space on my reading list. Published in paperback and electronic formats on 20th August by J.New Books, I thought it might intrigue and appeal to others too.

Nine stories

One artist

The whole world against himThe Nine Lives of Jacob Fallada is the story of an outsider, a lonely, misunderstood young artist who chronicles all the unpleasant things that happen to him in life. Abandoned by his parents, brought up be a tyrannical aunt, bullied at school, ostracized by the local community, nearly everyone Jacob comes into contact with takes an instant, (often) violent dislike towards him. Like Job from the bible, he is beaten and abused, manipulated and taken advantage of.

Life, people, fate, circumstance force him deeper into his shell, deeper into the cocoon of his fledgling artistic work, where he records every significant event in sketches, paintings and short-form verse, documenting his own unique, eminently miserable human experience. At heart, he longs for companionship, intimacy, love, but is dealt so many blows he is too scared to reach out to anybody. On the fringes of society, he devotes himself solely to his art.

So no review this time, but it’s a pleasure to welcome Neil Randall to Being Anne with a piece he’s called “Never Read the Instructions”, on the genesis of The Nine Lives of Jacob Fallada…

In the weeks before leaving high school, our deputy headteacher devised a short multiple-choice test to help pupils prepare for their final examinations.

“You have half an hour to complete this simple questionnaire,” he said, checking his wristwatch. “Remember to read the instructions very carefully.”

Eager to impress, to showcase my zeal and intelligence, I turned over the top sheet and read the first question.

1) Before attempting to answer any of the questions on this questionnaire (1-100) read each individual question through to the end (1-100).

Seeing this as a waste of time, I ignored the instructions and began to work my way through a strangely simplistic series of questions. What colour is the sky? Circling the word Blue, I moved on to the next: What is two plus two. Others, like Question 7, for instance, were even more perplexing:

7) Say: “I follow my teachers’ instructions to the letter” out loud.

This I did, in confident, assured tones, to show the deputy-head the rate of my progress. Not once, as I continued to speed through the rest of the questionnaire, did it strike me as odd that none of my fellow classmates shouted out the same sentence after me.

Only when I reached the end of the questionnaire, Question 100, did I find out why; did I realise my mistake.

100) Now you have read all questions, put your pen aside, sit quietly and await further instructions. You do not need to fill in this questionnaire. This test has been devised solely to teach you an important lesson in life: always read the instructions carefully. That way, you will avoid any foolish, unnecessary mistakes.

On reading that last fateful question I felt crushed; I wanted the room to swallow me whole. I daren’t look up, for fear of not only catching a harsh, disapproving glance from the deputy-head, but mocking looks from my far more conscientious classmates.

In many ways, the whole sorry scene summed up my entire school experience. Instead of encouraging pupils, nurturing their talents, the teachers were more interested in tripping them up or catching them out. Instead of devising a test to help children flourish, to showcase their skills, the deputy-head devised an exercise to embarrass and humiliate them, an exercise in conceit.

And I know that many people reading this won’t agree, that they’ll think that he succeeded in his objective: creating a clever, instructive test to show pupils the importance of reading instructions carefully. But to my mind it was designed solely to service his own sense of superiority, and was indicative of a far deeper malaise.

Back then, the education system had lost all sense of its true purpose. The school I attended, a crumbling secondary modern, had a supremely unmotivated workforce, during times of industrial action, strikes, Thatcher, the National Union of Teachers. Any talent or aptitude a pupil displayed was discouraged or simply ignored. The Nine Lives of Jacob Fallada is my eighth release, but I honestly can’t remember reading a single book all the way through to the end, the whole time I was at school. Regardless, I loved English classes, standing up and reading in front of my fellow pupils, sometimes putting on funny voices, performing to a certain extent, in the way younger people naturally do, without embarrassment or restraint, the self-consciousness which very much confines them to their shells when they grow older and life really grabs them by the throat. I was a gifted sportsmen – football, cricket, tennis, athletics, swimming – but the sports-masters treated each PE lesson as a platform on which they themselves were meant to shine.

Self-expression, the freedom to explore your own potential capabilities were roundly crushed, spat upon. Instead of letting a child’s natural creative streaks flourish, the teachers wanted to invent spurious restrictions, rules and regulations, just like that stupid multiple-choice test.

And I think it was probably memory of this, the anger at having so many doors slammed in my face at such a young age, which (many years later) provided the inspiration for the character of Jacob Fallada. In some respects, I see each of his nine lives (and I’m talking figuratively here) as representative of the talents I may have developed in the art or music room, in drama class, on the sports field or running track, but which were trampled underfoot, maybe the stolen talents of all my fellow classmates, too, or any child who enters the education system full of potential, only to have it routinely crushed by a bunch of bitter, mediocre, unfulfilled, spineless non-entities.

For that reason, as sad as Jacob Fallada’s fate is at the end of the book (and I won’t let anything further slip – you’ll have to read it if you want to know what happens to him), I do feel that anyone who has ever wanted to express themselves in life, just like Jacob with his sketches and poems, and who has met with nothing but discouragement, resistance, ambivalence, outright hostility, but still preserved, regardless, has a little of Jacob inside them. And that, to my mind, whether they are young, old, or hovering somewhere in between, is far from a bad thing, because it shows that those bastard teachers don’t win every time.

Never read the instructions. #IamJacobFallada

Giveaway

With thanks to the author, publisher and Rachel’s Random Resources, I’m pleased to offer the chance to win one of three copies of The Nine Lives of Jacob Fallada (UK only). Here’s the rafflecopter for entry:

Terms and Conditions UK entries welcome. The winner will be selected at random via Rafflecopter from all valid entries and will be notified by Twitter and/or email. If no response is received within 7 days then Rachel’s Random Resources reserves the right to select an alternative winner. Open to all entrants aged 18 or over. Any personal data given as part of the competition entry is used for this purpose only and will not be shared with third parties, with the exception of the winners’ information. This will passed to the giveaway organiser and used only for fulfilment of the prize, after which time Rachel’s Random Resources will delete the data. I am not responsible for despatch or delivery of the prize.

About the author

Neil Randall is the author of seven published novels and a collection of short stories. His work has been published in the UK, US, Australia and Canada